Beaumanor Civilians Remebered

This Page, authored by one of their number, Ken Carling, commemorates the civilian radio officers who served at Beaumanor Park between 1945 and 1970

Acknowledgement

My grateful thanks are due to Garats Hay – the website for the “Y” (Wireless Intercept) Services for hosting this article.

Preface

This article is an attempt to give some of my own personal recollections of the special work performed at Beaumanor Park.

Introduction

Beaumanor itself came under the auspices of the War Office and its official title was WOYG (War Office 'Y' Group). The Station was situated in the small village of Woodhouse near Loughborough and was one of the main wireless intercept stations during the war years.

Joan Nicholls, a young ATS girl at the outbreak of WWII, describes the life and work at Beaumanor during those years in her book “England Needs You. The Story of Beaumanor”. Her book was published in March 2000 and Joan deserves great credit for describing the life and work of the combined military and civilian 'Y' operators at Beaumanor in such detail. It makes fascinating reading and gave me the idea that the Beaumanor story should not end there. I pick up the story at the point where Joan’s book ends.

Onwards - From 1945

By the end of the war, the number of staff at Beaumanor had risen to some 900 ATS operators and 300 male, civilian wireless operators. An interesting mixture and a mind-bending ratio. But peacetime saw Beaumanor slip into neutral gear as its raison d’ètre appeared to have disappeared. A reversal of roles occurred as all the ATS girls were gradually demobbed, but 78 civvies (the gallant 78) who were liable for National Service changed into khaki and went off to “do” their required two years in the Forces. Most of the remaining, older civilians stayed on at Beaumanor and, eventually, most of the 78 came home there after National Service. The name of the Station altered from the old WOYG and now became WOCWS (War Office Civilian Wireless Station) and later WOWS (War Office Wireless Services) and yet again to WORS (War Office Radio Services). And then came the Cold War. “Beau” was back in business and a full complement of staff was required to fill the empty seats.

Recruiting for new operators started and a gradual flow of fresh recruits came into the job. Nearly all of these were ex-Services, with varying degrees of competence in wireless operating. Most certainly they were all male and so the interesting mix of the war years disappeared; which certainly was a shame.

My own case is typical of those joining at this period. I had done my National Service in the RAF and was trained as a wireless operator. Radio communications work suited me and I found it very interesting. At the end of the 28 week course at Compton Bassett I was posted to RAF Miho in Japan with the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (BCOF), I enjoyed the travel, my year in Japan and the point-to-point radio operating there. When the magical number of 73, (my demob batch number) came up in 1947 I found myself in civvie street back in the UK and unable to find any job associated with radio operating and finally finished up as a welder. But I continued to seek work as a radio operator and eventually an ex- Forces employment association pointed me in the direction of Beaumanor. I applied, and following a successful interview, started at Beaumanor in the summer of 1949.

Beaumanor had its own,local training establishment and most people only needed a couple of weeks to familiarise themselves with the peculiar necessities of 'Y' work. Some spent a couple of weeks at the nearby Royal Signals camp, Garats Hay, to bring their Morse copying speed up to 20 w.p.m. before going on to the Beaumanor course. This was when the penny dropped. New entrants realized that there was not a Morse key in sight. The job was receiving Morse and receiving Morse only. No sending skills were required. It seemed that we were only going to be half a radio operator, but it is more correct to say that we would become specialists in receiving Morse.

The trainees went from the training room in ‘J’ hut to the main set-room, ‘M’, where they polished up their new-found skills on what would later be called on-the-job-training. We knew it as ‘double-banking’ and would sit side-by-side with an older, more experienced operator to learn and/or be corrected when mistakes were made. It was a good and practical way of learning the ropes. Those early years are a continuation of the job described by Joan Nicholls in the same buildings and with the same equipment. The only thing that had altered was the target.

The life of the ‘normal’ 'Y' operator is the same as any other job - once one has shaken off the ‘new boy’ feel and settled in, then all becomes routine. 'Y' work can be more than very interesting but a great part of it is routine and boring and a 'Y' operator learns patience over the years. One must remember that the fundamental nature of the job means that a 'Y' operator cannot start work until some-one else does. The job involves waiting and listening for the target to do something. If the target does nothing, then the operator just sits. If the main target remained silent, then the operator was often given a supplementary task that could be ‘dropped’ if and when the priority target commenced transmission.

Most of the time is spent on shift work. The shift system at Beaumanor in 1949 was gruelling in the extreme. The system worked over a 28 day period, which started on a Monday night at 2200 hours as the first of 3 night shifts, then came a day off, 4 afternoons, day off, 7 mornings, 4 nights, day off, and closing with 3 afternoons. The last, third afternoon would end at 2200 hours on a Thursday.

The next three full days, Friday, Saturday & Sunday made a long week-end off duty and then the whole cycle re-commenced on Monday night. The actual hours of the shifts were 2200-0700, 0700-1400 and 1400-2200.

And all this for a young trainee’s pay of £3-10 shillings clear a week - with a maximum in the region of £6-4 shillings per week after 7 annual (Civil Service) increments.

Many of the new entrants took advantage, or had to take advantage, of the accommodation offered at Beaumanor Park itself for the princely sum of 2/6d (12½ pence) per week. Beaumanor had approximately 20 rooms on the two top floors of the Hall, which were set aside for the use of staff. A typical room would have 4 beds, with a wardrobe or cupboard allocated to each occupant’s ‘bed space’. Bedding was army style; three hard, uncomfortable “biscuits”, two pillows, maybe a pillow case and three rough blankets. Very much Forces style and a style with which most of the entrants were more than familiar as most probably they had just left something very similar. The living was rough, but for half a crown a week could be considered good value. Redeeming features included plenty of heat and big bathrooms with unlimited amounts of piping hot water. And, one extra special bathroom decorated in green and with several larger than life nudes on the walls. Had they been painted by an ATS artist?

There were no complaints really. Food was obtainable at the canteen and eaten in the grandeur of the spacious dining room. But, there was not much to spend on food - or anything else out of a weekly pay packet of £3. So eating became a luxury. Living includes other important things and one had to allow for the necessities of life such as cigarettes, beer, bus fares to and from Loughborough, the cinema and last, but not least, the famous dances at Loughborough Town Hall. Once in a while, for a special treat, and if prudent, a bus ride to the big cities of Leicester, Nottingham or Derby might be afforded.

There were a lot of resignations in the period that I joined. The throughput of trainees was enormous as people would endure this hard labour for only a couple of months and then go on to pastures new. The ones who stayed were either hard or hard-up - or both. But, there were some, the romantics?, who thought it a challenge and enjoyed the life. Great efforts were made by people such as Fred Phillips (CSU) to obtain an improved pay scale and success was finally achieved, but not for some years. Fred was something of a folk hero at Beaumanor - admired and respected for his toughness and tenacity in his dealings with the Official side.

The Job

Progress cannot be ignored. Morse sent on a normal hand key is reliable and a good operator can transmit (and be received) at an average speed of 20 words per minute. But by the late 1940s it was becoming considered a slow means of communication. Faster and more secure means of transmission were already available and employed on some networks. Radio Teleprinters using the international Murray code and variations of it became common and strange sounding transmissions such as Baudot were also employed. So Beaumanor operators learned how to receive and cover these “Non-Morse” or “NOMO” transmissions.

With time, hundreds of different variations of printer and similar Non-Morse transmissions were added to the 'Y' operator’s skills. In addition, scores of different types of subsequent modes of transmission came on the air and required cover. If it could be sent, then it could be received, and it was.

Direction finding (D/F) work was a specific and different type of intercept activity. The details of how D/F results are obtained have altered with the times, but the fundamentals still apply and some 'Y' operators would come to specialise in this field of work. “Field” can be taken literally as a D/F site was usually stuck in the middle of one!

Further

The existence at Beaumanor was changed to hopes of a proper life in 1949 when opportunities for overseas employment were announced and volunteers were called for. A mad rush ensued and the overseas waiting list became a well thumbed document as staff would chart their upwards progress in the list.

Most of the entrants had seen service overseas and were desirous of more. “How can you keep them down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree” applied. More inviting than the sun were the initials “FSA”. Two questions were uppermost : Where would you go? and What does FSA mean? Maps and dictionaries were much in demand. FSA, it turned out was Foreign Service Allowance, a means of paying a lot of money into the employee’s bank account for the inconvenience of having to leave the wintry shores of UK and live abroad. The declared policy laid down for the establishment of civilian 'Y' operators at overseas intercept sites was that the civilians would act as a stable, seasoned and professional body to counteract the churn-around of National Service operators. The latter would have done their basic training at Catterick then on to Special Operator training at Garats Hay (next door to Beaumanor) and might then be give foreign postings for about a year before being demobbed. So, they were just about fully trained when their National Service time ended and they left for UK and demob. The civilians were on a 3 year overseas tour and in the job for life. It transpired that some of us would subsequently do 3, 4 or 5 tours at foreign stations.

It must be said, and I was there, that the first batches of civvies were not popular. Very understandable as the Army operators were on a basic army wage of £2 to£3 per week and the lowest grade of civilian was earning some £12 per week. The young Army operators were fully aware of the difference in pay and thought it unjust that the civvies were getting more for doing the same job. Another bone of contention was that Radio (Wireless) Operating was not a soldier’s main job. He was first and foremost a soldier but also a Signals 'Y' operator and therefore found himself wearing two hats. He could be on a spell of guard duty, come off that, put his rifle away, pick up his headphones and straight on to a morning, afternoon or night shift in the set-room. I could empathise with them as I myself had only just completed my own National Service. I tried to put forward the argument that they only had to wait for a year, get demobbed and re-apply for Beaumanor as a civilian. But a “wait of only a year” is a lifetime for a 19 year old and so my words of advice fell mostly on stony ground. That said, life went on and gradually the civilians became a fact of life and duly accepted as part of the order of things.

Civilian operators on overseas service were almost always automatically given the equivalent rank/grade of Sergeant and thus allowed to join the WO/Sgts Mess. A privileged few, some twenty in number, were further allowed to put themselves forward for selection as a Full member of the Mess. In this way I became a full member with the right, if I so wished, to attend Mess meetings and vote according to my wishes. Again, and again, understandably - there was some slight resistance to civilians being given this right. But the general mood of the Mess members was one of acceptance and we were gradually assimilated into Mess life. I thought it an honour to have been given the privilege, and still consider that the 10 years spread over three tours as a Royal Signals civvie count as one the best parts of my life. This was due in no small way to Mess life and the great pleasure of associating with some of the finest people I have ever met. A senior NCO in any of the armed forces, Army, Navy or Air Force is without equal.

Beyond

And so, from 1949, the pattern of a 3 year posting abroad, return home to Beaumanor, perhaps a course or up-grade of training at what we knew as CTS (Central Training School) but is now more famous as Bletchley Park and then off to foreign parts for another tour. Wonderful days. It was famously said during this time (guess who?) “You’ve never had it so good”. It was certainly true in our case. The set rooms at Beaumanor are well described in Joan Nicholls book, but the first civilians arriving at overseas stations often found conditions primitive in the early days.

Development invariably occurred however, and throughout the early 1950s working conditions steadily improved. Set rooms in due course acquired huge dimensions and were often split into two or more accommodation spurs. Civvies would sometimes be located one of the large sections and the Royal Signals “spec” ops occupied the others. The original plan of work for many sites included a couple of so-called Key positions manned by the more experienced civvies who would intercept the required targets and feed them out to the Army operators. Other than that, the Army and Civvie operators carried on with their own laid down tasking of cover. Royal Signals operators were responsible for all D/F and Intelligence Corps personnel carried out most of the traffic analysis and reporting. Integration of smaller units gradually came more often as cover changes demanded with a very good example of an Intelligence Corps voice Operator and a civilian Morse operator working literally side-by-side on the same target. Each to his own, but both together.

1965 - Signs of Change

All good things come to an end - and so it did in 1965 - when we were informed that a thing called Integration was to be thrust upon us. All Beaumanor civilians then overseas would no longer be automatically returning “home” after their tour but would be offered a preference of one of three other UK 'Y' Stations as their permanent, new home station. This period saw unification of intercept work under a single, national authority in the form of GCHQ Cheltenham.

I happened to be on my third tour and due to return to UK and Beaumanor - of course. But, not now. It was a blow but 'orders is orders'. I was obliged to select a new 'home' from a short list of available candidate stations. It was strange to be in a new and unfamiliar one and covering brand new targets but there was no trouble settling in. The greatest problem was arriving in a strange town at the height of a busy summer season complete with wife and four children, but nowhere to live. My old Beaumanor colleagues were, of course, duplicating my own experience in all the other UK stations.

1970 - Final

Beaumanor civilians, whether at home or abroad were, on the whole, a happy band and one of mixed talents. Besides their undisputed professional skills, most of the operating staff had been in some form of trade before the outbreak of war and most had served in H.M. Forces during the war - or had ‘done’ their National Service after the war ended. They were intelligent and they were gifted - very gifted. They were quick to learn the many and varied skills during their years in a highly demanding job. They were denied one of the most normal and simplest of things - being able to talk about the job after they left their work place. For the most part they worked shifts which required them to sit in front of a wireless set every fourth night of their time in the job. Note : the wireless set came to be known as a radio, but Naval intercept stations in particular were always referred to as a “Wireless Station “ and it remains so at some locations to this day.

The break-up of "the family” had started in 1965 and ended five years later in July 1970 when Beaumanor, by now down to a skeleton staff, closed the doors of the set-rooms for the last time. The Manor itself would later be acquired by Leicestershire County Council and completely refurbished. It would re-emerge as a teachers' training college and then a conference centre. The new national authority had claimed that 'Y' stations under separate controlling bodies were getting in each others' way with duplication of cover etc. They maintained that under one control, theirs, that everything would be super-efficient. It could be argued that the authority’s “big is beautiful” idea was false and that the idea of integration was not necessary and was not a good idea.

We were promised that we would keep the best and inherit better!

There was no going back. It had been done. Beaumanor staff was now dispersed at one or other of the UK 'Y' stations or in service overseas at an ever-shrinking number of stations. They would still be found alongside military operators, but they would no longer go home to Beaumanor Park.

Postscript

Thirty years after Beaumanor closed for official business its name came back to life again – in October 2000 – in the form of one of “Smartgroups” many thousands of web sites.

The Beau Smartgroup ran successfully until October 2006 when Smartgroups gave one month's notice to all its groups' and announced that they would terminate their services on 30th November 2006.

In its six years of existence the Beau group had gained a membership of nearly 80 members in various parts of the UK and the world.

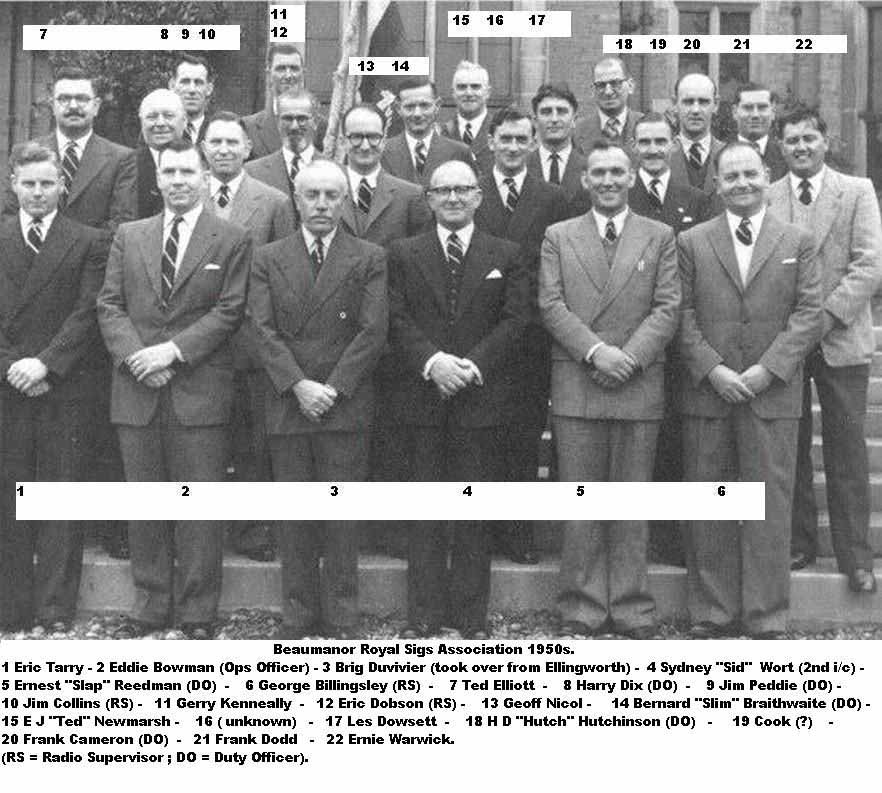

The members had exchanged nearly 12,000 group E-mails and a photo library of some 600 photos had been created.

Conclusion

The Beaumanor web site has been lost but group members still remain in contact via E-mails.

All of the photos from the defunct web site, and new ones added since then, have been saved and stored - thanks to the work of Cliff Needham and Brock Tomlinson.

Readers who have found this article on the Garats Hay web site and interested in the subject are welcome to contact Ken at kclcar@btinternet.com

==============

Ken Carling, ex Beau Y operator, now 'looker-after' of the Beaumanor archives.

Kenneth Carling - ©2014